Classifying Handwritten Digits

Given a set of computer generated digits with a consistent font, it wouldn’t be terribly difficult to design an algorithm that accurately classifies every digit. The challenge of classifying human written digits, however, seems daunting. Humans write with vastly different styles: some people put dashes through their 7s and 0s; some people connect the top of their 4’s while other’s don’t; digits come squished and stretched, tilted and straight… A simple logical procedure of “if this, then this” would never work very well with such variation.

This is a classic use case for machine learning. (And hence a great project for a data science bootcamp!).

The MNIST data set provided a set of 60k images of handwritten digits to train and test our machine learning algorithms on. We (me and a team of 3 others) also added other sources of digits to our training set, expanding it to around 75k digits. Initially, we tried breaking each digit image into a set of about 15 features, including simple statistical features like mean horizontal/vertical position of activated pixels (the center of mass of the digit releative to the center of the digit’s bounding box), digit symmetry, total size of the digit, radial moment of intertia, and average number of edges when treversing from left to right and down to up. We then applied a host of classifiction algorithms on this feature set: Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine, Naive bayes, and Random Forrest. Ultimately, Random Forrest generated the best result, with 91% of the MNIST test data accurately identified by the model.

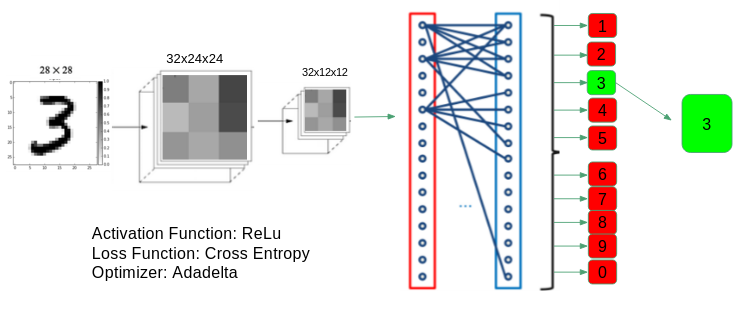

However, 91% isn’t enough to be very USEFUL. Given an image of digits, the resulting text scan would be full of typos and hardly worthwhile. So we shifted to a new method: Convolutional Neural Networks. “Convolutional” refers to the initial convolution step of the process, in which the image is convolved with a set of kernals, each with a small receptive field. The convolutional layer is great for image identification because it is translationally invariant and focuses on locally connected features. In other words, the position of the digit in the image is irrelevant, and pixels on opposite side of the image do not strongly influence each other in the learning process, as opposed to a more traditional fully connected neural network.

Our convolutional neural network led to a 99.2% accuracy on the MNIST data set! We used “Keras” to build the network, an awesome python library written on top of TensorFlow.

We wanted to turn our classifying software into an at least somewhat useful product, so we decided to expand the scope of our project. We figured it might be useful if you could automatically read many digits in an image. Given a page full of digits, could we segment and classify each digit automatically? In college, I’d often end up with tables of hand written numbers after running a physics experiment, and had to later manually type them all into excel for data analysis. Thus, we were inspired to create a “tablizer” that could scan, classify, and arange every digit into a digital table that could easily be imported into excel.

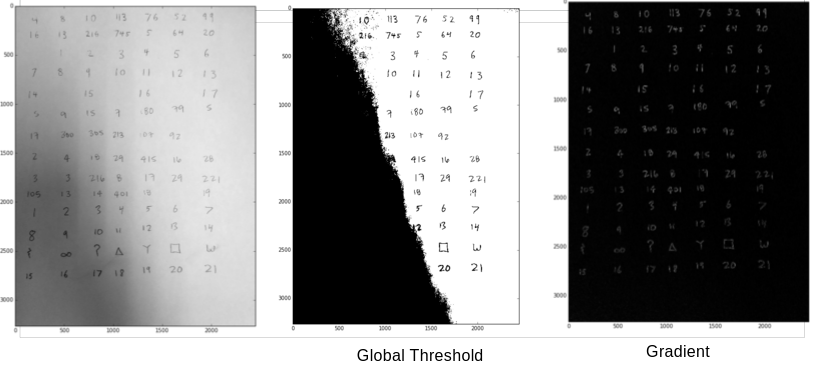

The primary challenge was segmenting indiviudal digits in an image before passing them off into our neural network. First, we binarized the image. This wasn’t as easy as it seems; shading variation in an image often made it impossible to choose a global threshold to binarize the image on (pixel values below thresh -> 0, pixel values above -> 1). See the middle photo below. To get around this, we apply the “sobel” operator. It essentially finds the gradient/derivative/rate of change of the image. Consequently, regions that quickly transition from one intenisty to another pop out – It’s an edge detector! This caused the shading variation to drop out and the digits to clearly pop out on the page. Binarizing this new image was then feasible.

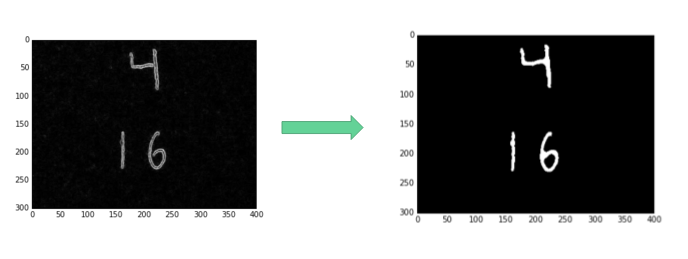

After applying the gradient, we’re left with a bunch of outlined digits and other noise. The neural network was trained on a set of solid digits, so simply passing these outlines into the network would not result in very accurate identification. To get around this, we applied a few morphological operations: mainly “closing”, “filling,” and removal of small spurious pixel blobs in the hopes of only leaving behind actual digits. Below is an example of that process.

With this final image, we can label each isolated blob of connected pixels, segement them, and pass them off to our classifacation model!

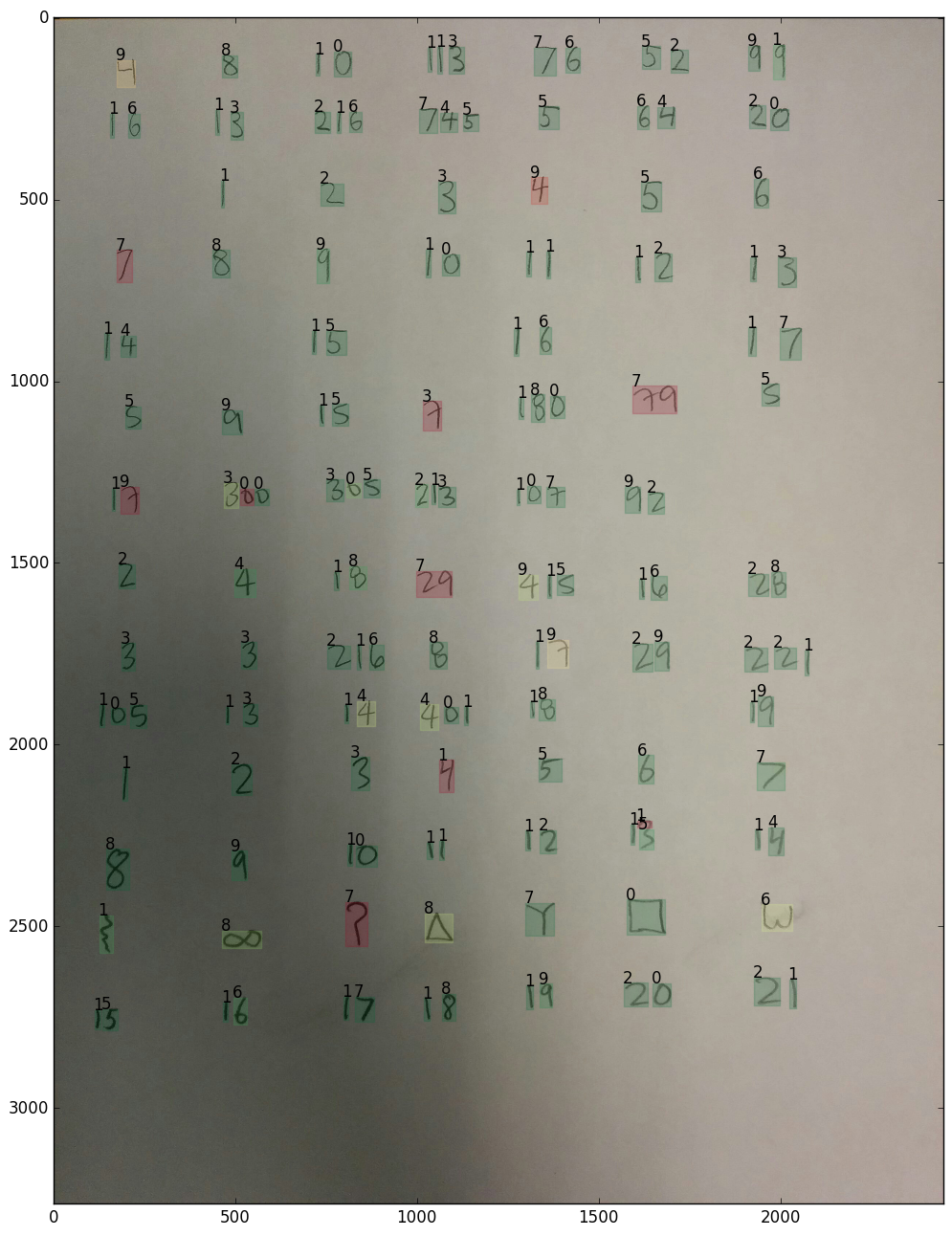

Here’s some example output. The predicted number is printed above each handwritten digit. The color corresponds to the confidence of the classification: green means the neural network was very certain, red means it probably guessed wrong.